In the German language we have a beautiful word: Heimat. The English language has the word home, but Heimat encompasses more. Home can be anywhere, but “Heimat” is where you belong. It’s deeper. I grew up in Stuttgart, in the south of Germany, but even as a child, I knew that I would not stay in there – Stuttgart never was Heimat for me. It was just a home. This book is about St. Pauli, the small hood near Hamburg’s harbor, that became my true Heimat.

There is a song from Hans Albers, written in the 1950s, called “The Heart of St. Pauli.” It is the story of a sailor who always returns to St. Pauli because the heart of St. Pauli calls him back. I feel like that sailor. I left to see the world and have been working in New York City since 2015. New York City gave me a lot, for which I am grateful, and has made shaped me into a true working artist. Yet, during all these years, I always returned to Hamburg. The heart of St. Pauli keeps calling me back.

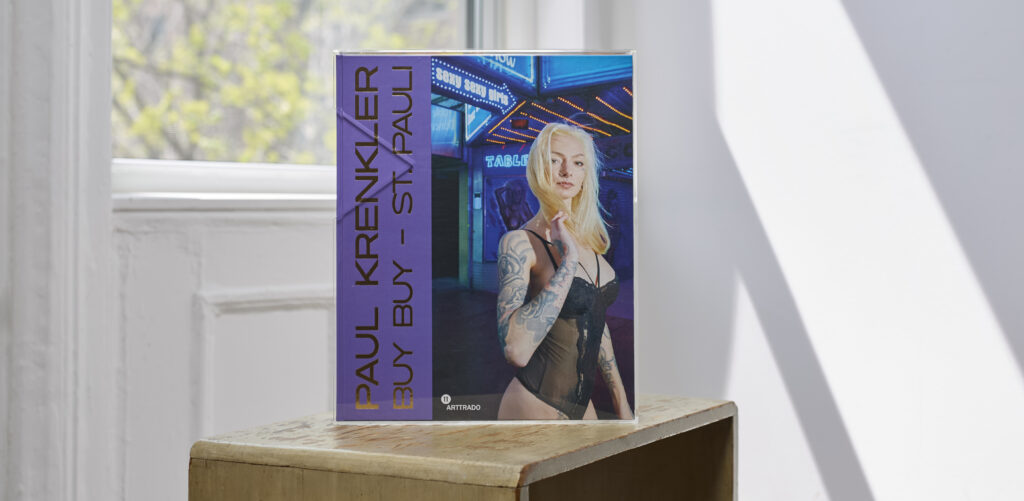

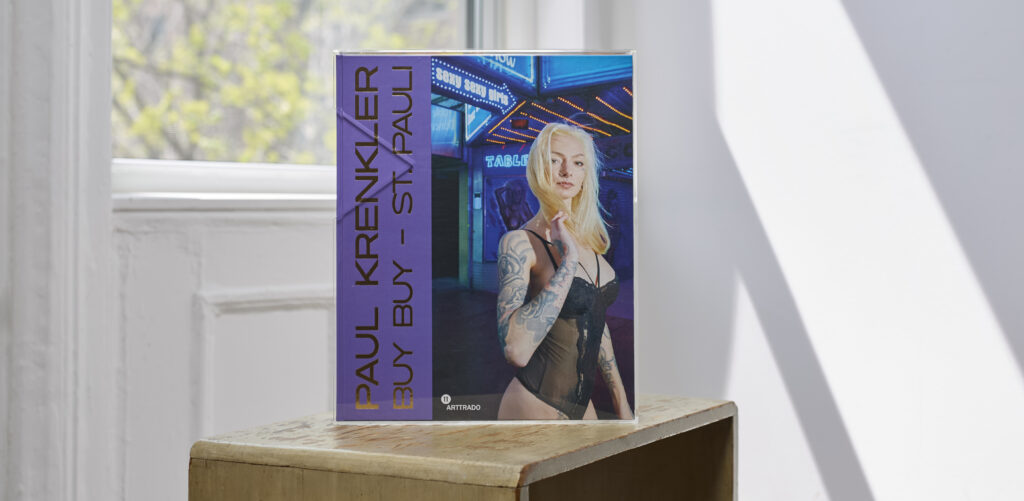

The title of this book is indeed in English: “Buy Buy – St. Pauli.” There is no way to translate it into German. When spoken in English, “Buy Buy…” sounds like both buying and goodbye. A fitting double entendre, since this book is about gentrification, illustrating the sellout of my unique and charming neighborhood. What will remain? No one knows, but I wanted to honor my hood and show the world how wonderful this place is. This book is my love letter to St. Pauli.

PAUL KRENKLER

DR. ANDREW SPANO is the author of books on psycholinguistics and the publisher of Atropos Press Balkan.

He was born and raised in New York City, he lives actually in Belgrade.

In the 1939 Hollywood movie The Wizard of Oz — there’s a scene where Dorothy and her crew, the Tin Man looking for a heart, the Scarecrow looking for a brain, and the Cowardly Lion looking for courage, go to see The Wizard. Also known as the Great and Powerful Oz, he is the one, they are told by the local peons of Emerald City, that can grant their wishes. Dorothy wants to go “home” to Kansas. But the fact is, all four of them are homeless. What’s left of Dorothy’s actual house was blown up into the air by a tornado. The other three seem to sleep wherever they can.

As they tremble before a giant altar that’s supposed to be Mr. Great and Powerful, listening to it thunder about how great and owerful it is, Toto, her “little dog,” as the Wicked Witch of the West calls him, bites the bottom of a curtain, and pulls it back. There stands a nervous little man looking every bit the part of an old-fashioned bamboozling, swindling, hornswoggling, flimflamming, hoodwinking con artist. He turns to discover that his fraud has been revealed, and says through the Great and Mighty loudspeaker, “Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain!”

But it’s too late. The jig is up. They’ve seen through his phony game.

For the past seven years I’ve been admiring looks on the faces of the people in the sublime photographs of CP Krenkler, or Paul, as I know her, as she documented the dispossessed of the St. Pauli district of Hamburg in the Hamburg-Mitte borough containing the Reeperbahn, which is, or was, for all intents and purposes, the Land of Oz, only lit with red light. The images show people of intense character who are shaped by and who shape that environment infamous to some and beautiful to others. And they show the progressive struggle these residents enduredto reconcile their lives with a sea change in the Zeitgeist, the spirit of the times, that made them outcasts in the Emerald City they loved because it was where they felt they belonged.

Only a rare photographer with Paul’s unique artistic vision could have gone the critical step beyond the process of documentation into the making of those faces, those bodies, those tattoos, those bars, and those moments real forever – just as they were vanishing. She was as much a part of it as they were, but with that magic ability to step outside of it to show us what it is and was, but not, alas, what it will be.

It isn’t just her ability to bring the times and lives of her friends, neighbors, acquaintances and a whole famous and infamous part of a great city that has moved me in these images. I am drawn in by the reason why it happened, and because this is something I have witnessed now twice on a grand scale in two cities as great as Hamburg: Boston and New York, over a twenty-year period. It is usually called “gentrification.” But this word is misleading. It almost sounds natural and … gentle. The true phenomenon is called financialization, and it’s destroying not just neighborhoods and the lives of those within them, but nations and cities of the world, never mind the environment and the fabric of a decent human life in the process, everywhere.

What is it? Behind the solidity of the buildings we live in and the ground we walk upon are financial instruments now being traded as commodities and gambled as bets in the world’s complex financial markets. They even include the medicine we’re now forced to take, the minerals that make our energy, and the crops that feed us. EVERYTHING has been financialized, even the weather, the outcomes of democratic elections, and football games. The world is now one great big gambling casino. The only problem is that you must be a high roller to get in the door. If you’re not, then you’re merely a chip on the velvet to be cashed in at the end of the game.

The people you see in these pictures, and probably you and I, are the chips to be cashed in. But for those who the French call the “outré,” the Outsiders, or who Marx called the lumpen proletariat, of the Emerald City’s red-light district, their “chip value” is negative, meaning that they are only worth something once they have been gotten out of the way. This book is a chronicle of such a purge. And it is a mistake to think that because you are not living on the edge of mainstream culture, as many of these people are (or were), that you are immune to the hornswoggling and bamboozling of the Great and Powerful Oz. You’re next, comrade.

How do I know? Well, let me tell you about my experience.

In 1998 I moved into Boston’s Chinatown down near the waterfront. I’d lived in Boston on and off since I first got there in 1978. Now, I was teaching at a university there, and some colleges. Ever since 1974, when there were riots in the neighborhood in opposition to what was then known as “school bussing” – an attempt to end de facto segregation of the Boston schools – the area around Chinatown was known as the Combat Zone.

But it was much more than that. It was home to hives of the outré and the lumpen proletariat: drug dealers, prostitutes, pimps looking like they just stepped out of the Superfly movie, underground techno parties, artists, musicians, dive bars, transexuals, transvestites (as they were called then), gay porno theatres, mouthwash drinkers, heroin addicts, erotic shops, strip joints, and two homeless shelters with a skid row leading from one to the other.

The irony did not escape me of the fact that the famous Liberty Tree, where the colonists had staged their first “act of defiance” against their British masters, had stood in the midst of the Combat Zone, next to (of course) the Liberty Tree porno, peep show, and sex toy shop.

I was in my own Land of Oz! I won’t explain why I loved it except to say that I’ve always felt most comfortable living on a street with people that I felt were LIKE ME. I inherited my flat from a stripper at the Golden Slipper and proceeded to become an integral part of this … magic, NOT tragic, community. At the same time, I was part of another community just across the bridge in Fort Point Channel where a certain queen owned most of the formerly mercantile buildings that were now artists’ studios. Between the two places my life was a tornado, as Dorothy would say, of art openings, all-night dance parties, fascinating friends and acquaintances, and the production of music and art. The fact that it all had Chinatown as its core, made the experience absolutely sublime. It transformed me in ways I’m still trying to understand and will always be grateful for.

But then in September 2001 the World Trade Center in New York City was attacked and destroyed by Al-Qaeda jihadis. Though our little island of Boston’s own Reeperbahn was two hundred and fifty kilometers away from that, it had its effect: the local and national economy collapsed. For a while I was the only tenant on my floor in a 150-year-old building on Tyler Street. What I didn’t know was that the world as I knew it was being bought out from under me at what they call in the financial industry “fire-sale” prices, thanks to Osama bin Laden, et al., with “stimulus” money printed up by my government and ones around the world. At the same time, Americans and their counterparts elsewhere were surrendering their freedoms to their governments and begging for More National Security. Of course, what this meant was first getting rid of the lumpen proletariat, the outré, the artists, and their industries. Enter: Financialization.

Blocks were bulldozed. Bums were scattered to the corners of the city. Pimps went south with their stables. Porn shops closed. Bars shriveled up and died after a smoking ban. Property value inflation set in as the government banks and real-estate speculators turned brick, mortar, and dirt (in this case stained “with the blood of patriots”) into paper commodities to be traded on the global high-risk markets. High-rise towers sprang up where little Chinese restaurants used to be. Rents soared. All artists except the few in Fort Point Channel who could afford to buy their studios were pushed into other cities and even states and countries as the Queen exercised her Royal Power to financialize (gentrify) what were once artists’ studios.

There was no one to appeal to, except a few chroniclers like Paul of this destruction of what had been a good, solid, economic part of the city for decades with lower crime than many other parts of the city that had none of these, shall I say, cultural institutions. The misfits must go! Worst of all, we were admonished to “Pay No Attention to that Man Behind the Curtain.” We had to make- believe that being on the edge of homelessness, when just a few years earlier we were secure and content, was all part of the Great and Powerful Oz’s plan for a better world.

At last, I was forced to flee … to New York City. I got a job and a brownstone apartment in the ‘hood where Chris Wallace, a.k.a. Notorious B.I.G., the man who wrote the Ten Commandments of Crack, used to roll. I felt I’d made a pretty soft landing in another street full of freaks, weirdoes, drug dealers, prostitutes, eccentrics, and a whole new cast of creative misfits like myself. I made lots of lifelong friends right away. And, once again, the core of it was a neighborhood of rich cultural heritage from the African-American Diaspora, the Caribbean, and West Africa. Instead of being between two homeless shelters, I was between two mosques. I felt I’d made a successful escape, if not a slight improvement in my circumstances.

Then, oh then, came Global Financial Crisis 1.0 of 2008. You see, comrade, all that fake money that was used to buy up Chinatown and Hamburg and a thousand other places after September 2001 during the fire sale hosthcaused by Al-Qaeda so that the mortgages could be gambled on the international derivatives market now had to be PAID BACK to the banks. But there was no real money to pay for it. I think you know the rest of the story, unless you were living under a rock at the time. I’ll stop here, because this book is about the St. Pauli district of Hamburg, in the Hamburg-Mitte borough, containing the Reeperbahn, not Chinatown Boston, or Bedford-Stuyvesant, in Brooklyn. And it’s about Paul’s magnificent, moving, and jubilant and tragic images of just exactly what I’m talking about here, only someplace else … someplace else … YOUR place else.

In the movie, the Wizard tells Dorothy that if she closes her eyes and clicks the heels of her magic shoes together three times, chanting, “There’s no place like home,” she’ll be magically returned to Kansas. We who have loved and lived in such integral parts of all great cities that contribute more to the cultural life of humanity than office tower blocks, Wall Streets, High Streets, and luxury flats, don’t have magic shoes. We live in the real world, where you don’t get those shoes. If there’s a tragedy in any of this, and if we can see it in the faces of the residents of St. Pauli, it’s that they DARED to live in reality as the rest of the world drifted off into a dreamworld of greed, consumerism, imaginary fears, and a life dictated by insurmountable debt and political corruption.

What, then, is left to keep it real? What do we have to show after the tide has washed our homes and possessions out to sea, forever? We have these photographs, that are a gift both to the present and future, so that we don’t forget where we came from, and what it means to be merely human, as the people you see in Paul’s photographs will always be

In the German language we have a beautiful word: Heimat. The English language has the word home, but Heimat encompasses more. Home can be anywhere, but “Heimat” is where you belong. It’s deeper. I grew up in Stuttgart, in the south of Germany, but even as a child, I knew that I would not stay in there – Stuttgart never was Heimat for me. It was just a home. This book is about St. Pauli, the small hood near Hamburg’s harbor, that became my true Heimat.

There is a song from Hans Albers, written in the 1950s, called “The Heart of St. Pauli.” It is the story of a sailor who always returns to St. Pauli because the heart of St. Pauli calls him back. I feel like that sailor. I left to see the world and have been working in New York City since 2015. New York City gave me a lot, for which I am grateful, and has made shaped me into a true working artist. Yet, during all these years, I always returned to Hamburg. The heart of St. Pauli keeps calling me back.

The title of this book is indeed in English: “Buy Buy – St. Pauli.” There is no way to translate it into German. When spoken in English, “Buy Buy…” sounds like both buying and goodbye. A fitting double entendre, since this book is about gentrification, illustrating the sellout of my unique and charming neighborhood. What will remain? No one knows, but I wanted to honor my hood and show the world how wonderful this place is. This book is my love letter to St. Pauli.

PAUL KRENKLER

DR. ANDREW SPANO is the author of books on psycholinguistics and the publisher of Atropos Press Balkan. He was born and raised in New York City, he lives actually in Belgrade.

In the 1939 Hollywood movie The Wizard of Oz — there’s a scene where Dorothy and her crew, the Tin Man looking for a heart, the Scarecrow looking for a brain, and the Cowardly Lion looking for courage, go to see The Wizard. Also known as the Great and Powerful Oz, he is the one, they are told by the local peons of Emerald City, that can grant their wishes. Dorothy wants to go “home” to Kansas. But the fact is, all four of them are homeless. What’s left of Dorothy’s actual house was blown up into the air by a tornado. The other three seem to sleep wherever they can.

As they tremble before a giant altar that’s supposed to be Mr. Great and Powerful, listening to it thunder about how great and owerful it is, Toto, her “little dog,” as the Wicked Witch of the West calls him, bites the bottom of a curtain, and pulls it back. There stands a nervous little man looking every bit the part of an old-fashioned bamboozling, swindling, hornswoggling, flimflamming, hoodwinking con artist. He turns to discover that his fraud has been revealed, and says through the Great and Mighty loudspeaker, “Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain!”

But it’s too late. The jig is up. They’ve seen through his phony game.

For the past seven years I’ve been admiring looks on the faces of the people in the sublime photographs of CP Krenkler, or Paul, as I know her, as she documented the dispossessed of the St. Pauli district of Hamburg in the Hamburg-Mitte borough containing the Reeperbahn, which is, or was, for all intents and purposes, the Land of Oz, only lit with red light. The images show people of intense character who are shaped by and who shape that environment infamous to some and beautiful to others. And they show the progressive struggle these residents enduredto reconcile their lives with a sea change in the Zeitgeist, the spirit of the times, that made them outcasts in the Emerald City they loved because it was where they felt they belonged.

Only a rare photographer with Paul’s unique artistic vision could have gone the critical step beyond the process of documentation into the making of those faces, those bodies, those tattoos, those bars, and those moments real forever – just as they were vanishing. She was as much a part of it as they were, but with that magic ability to step outside of it to show us what it is and was, but not, alas, what it will be.

It isn’t just her ability to bring the times and lives of her friends, neighbors, acquaintances and a whole famous and infamous part of a great city that has moved me in these images. I am drawn in by the reason why it happened, and because this is something I have witnessed now twice on a grand scale in two cities as great as Hamburg: Boston and New York, over a twenty-year period. It is usually called “gentrification.” But this word is misleading. It almost sounds natural and … gentle. The true phenomenon is called financialization, and it’s destroying not just neighborhoods and the lives of those within them, but nations and cities of the world, never mind the environment and the fabric of a decent human life in the process, everywhere.

What is it? Behind the solidity of the buildings we live in and the ground we walk upon are financial instruments now being traded as commodities and gambled as bets in the world’s complex financial markets. They even include the medicine we’re now forced to take, the minerals that make our energy, and the crops that feed us. EVERYTHING has been financialized, even the weather, the outcomes of democratic elections, and football games. The world is now one great big gambling casino. The only problem is that you must be a high roller to get in the door. If you’re not, then you’re merely a chip on the velvet to be cashed in at the end of the game.

The people you see in these pictures, and probably you and I, are the chips to be cashed in. But for those who the French call the “outré,” the Outsiders, or who Marx called the lumpen proletariat, of the Emerald City’s red-light district, their “chip value” is negative, meaning that they are only worth something once they have been gotten out of the way. This book is a chronicle of such a purge. And it is a mistake to think that because you are not living on the edge of mainstream culture, as many of these people are (or were), that you are immune to the hornswoggling and bamboozling of the Great and Powerful Oz. You’re next, comrade.

How do I know? Well, let me tell you about my experience.

In 1998 I moved into Boston’s Chinatown down near the waterfront. I’d lived in Boston on and off since I first got there in 1978. Now, I was teaching at a university there, and some colleges. Ever since 1974, when there were riots in the neighborhood in opposition to what was then known as “school bussing” – an attempt to end de facto segregation of the Boston schools – the area around Chinatown was known as the Combat Zone.

But it was much more than that. It was home to hives of the outré and the lumpen proletariat: drug dealers, prostitutes, pimps looking like they just stepped out of the Superfly movie, underground techno parties, artists, musicians, dive bars, transexuals, transvestites (as they were called then), gay porno theatres, mouthwash drinkers, heroin addicts, erotic shops, strip joints, and two homeless shelters with a skid row leading from one to the other.

The irony did not escape me of the fact that the famous Liberty Tree, where the colonists had staged their first “act of defiance” against their British masters, had stood in the midst of the Combat Zone, next to (of course) the Liberty Tree porno, peep show, and sex toy shop.

I was in my own Land of Oz! I won’t explain why I loved it except to say that I’ve always felt most comfortable living on a street with people that I felt were LIKE ME. I inherited my flat from a stripper at the Golden Slipper and proceeded to become an integral part of this … magic, NOT tragic, community. At the same time, I was part of another community just across the bridge in Fort Point Channel where a certain queen owned most of the formerly mercantile buildings that were now artists’ studios. Between the two places my life was a tornado, as Dorothy would say, of art openings, all-night dance parties, fascinating friends and acquaintances, and the production of music and art. The fact that it all had Chinatown as its core, made the experience absolutely sublime. It transformed me in ways I’m still trying to understand and will always be grateful for.

But then in September 2001 the World Trade Center in New York City was attacked and destroyed by Al-Qaeda jihadis. Though our little island of Boston’s own Reeperbahn was two hundred and fifty kilometers away from that, it had its effect: the local and national economy collapsed. For a while I was the only tenant on my floor in a 150-year-old building on Tyler Street. What I didn’t know was that the world as I knew it was being bought out from under me at what they call in the financial industry “fire-sale” prices, thanks to Osama bin Laden, et al., with “stimulus” money printed up by my government and ones around the world. At the same time, Americans and their counterparts elsewhere were surrendering their freedoms to their governments and begging for More National Security. Of course, what this meant was first getting rid of the lumpen proletariat, the outré, the artists, and their industries. Enter: Financialization.

Blocks were bulldozed. Bums were scattered to the corners of the city. Pimps went south with their stables. Porn shops closed. Bars shriveled up and died after a smoking ban. Property value inflation set in as the government banks and real-estate speculators turned brick, mortar, and dirt (in this case stained “with the blood of patriots”) into paper commodities to be traded on the global high-risk markets. High-rise towers sprang up where little Chinese restaurants used to be. Rents soared. All artists except the few in Fort Point Channel who could afford to buy their studios were pushed into other cities and even states and countries as the Queen exercised her Royal Power to financialize (gentrify) what were once artists’ studios.

There was no one to appeal to, except a few chroniclers like Paul of this destruction of what had been a good, solid, economic part of the city for decades with lower crime than many other parts of the city that had none of these, shall I say, cultural institutions. The misfits must go! Worst of all, we were admonished to “Pay No Attention to that Man Behind the Curtain.” We had to make- believe that being on the edge of homelessness, when just a few years earlier we were secure and content, was all part of the Great and Powerful Oz’s plan for a better world.

At last, I was forced to flee … to New York City. I got a job and a brownstone apartment in the ‘hood where Chris Wallace, a.k.a. Notorious B.I.G., the man who wrote the Ten Commandments of Crack, used to roll. I felt I’d made a pretty soft landing in another street full of freaks, weirdoes, drug dealers, prostitutes, eccentrics, and a whole new cast of creative misfits like myself. I made lots of lifelong friends right away. And, once again, the core of it was a neighborhood of rich cultural heritage from the African-American Diaspora, the Caribbean, and West Africa. Instead of being between two homeless shelters, I was between two mosques. I felt I’d made a successful escape, if not a slight improvement in my circumstances.

Then, oh then, came Global Financial Crisis 1.0 of 2008. You see, comrade, all that fake money that was used to buy up Chinatown and Hamburg and a thousand other places after September 2001 during the fire sale hosthcaused by Al-Qaeda so that the mortgages could be gambled on the international derivatives market now had to be PAID BACK to the banks. But there was no real money to pay for it. I think you know the rest of the story, unless you were living under a rock at the time. I’ll stop here, because this book is about the St. Pauli district of Hamburg, in the Hamburg-Mitte borough, containing the Reeperbahn, not Chinatown Boston, or Bedford-Stuyvesant, in Brooklyn. And it’s about Paul’s magnificent, moving, and jubilant and tragic images of just exactly what I’m talking about here, only someplace else … someplace else … YOUR place else.

In the movie, the Wizard tells Dorothy that if she closes her eyes and clicks the heels of her magic shoes together three times, chanting, “There’s no place like home,” she’ll be magically returned to Kansas. We who have loved and lived in such integral parts of all great cities that contribute more to the cultural life of humanity than office tower blocks, Wall Streets, High Streets, and luxury flats, don’t have magic shoes. We live in the real world, where you don’t get those shoes. If there’s a tragedy in any of this, and if we can see it in the faces of the residents of St. Pauli, it’s that they DARED to live in reality as the rest of the world drifted off into a dreamworld of greed, consumerism, imaginary fears, and a life dictated by insurmountable debt and political corruption.

What, then, is left to keep it real? What do we have to show after the tide has washed our homes and possessions out to sea, forever? We have these photographs, that are a gift both to the present and future, so that we don’t forget where we came from, and what it means to be merely human, as the people you see in Paul’s photographs will always be